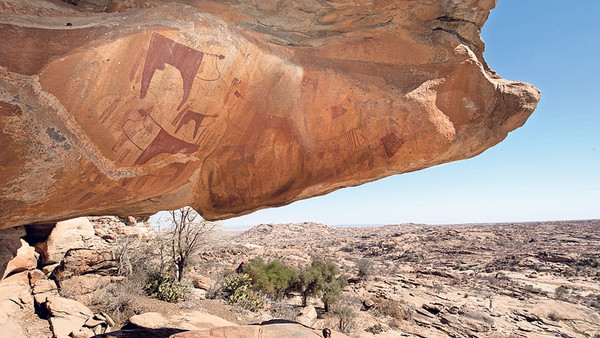

Rock art at Laas Geel

On the road to the Arabian Sea, the surface of the desert looked like a dinosaur’s hide: desiccated, calloused, cracked. In the middle distance were a cluster of nomad tents, like old haystacks. A gully opened and I glimpsed camels strolling in the sand boulevard of a dry river bed.

“Salaam,” Mahmud muttered, gazing out at vast reaches of nothingness as he shifted his AK-47 between his knees. “Sweet, sweet peace.”

“Where are the insurgents, Mahmud?” I asked. “Where are the troublemakers?”

He laughed dreamily. The qat had kicked in several miles back. “You are thinking of another country, my friend, another country.”

There are two Somalias, like two brothers in an allegory, contradictory temperaments springing from the same parentage, the Jacob and Esau of the Horn of Africa. Everyone is aware of war-torn Somalia, where gangs of young men ride round in 4x4s eagerly machine-gunning one another. Few are aware of its good twin, Somaliland, peaceful, law-abiding, a country with taxes, traffic lights and even tourists.

Both are former protectorates — British Somaliland and Italian Somalia — which gained their independence within days of each other in the summer of 1960. In a rush of idealism about a Greater Somalia, Somaliland immediately opted to join its larger neighbour, the new Republic of Somalia. Things did not go well. As the country degenerated into civil war in the late 1980s, tens of thousands died in the former provinces of British Somaliland and many more fled to refugee camps in Ethiopia. In May 1991, Somaliland finally escaped the bloody clutches of its war-torn brother as it issued a unilateral declaration of independenceand reverted to the sovereignty it had enjoyed for only five days 30 years before.

Somaliland can argue that its borders go back to the Berlin Conference of 1884-85 but, to the African Union, its declaration of independence looked like secession. The Union has always held to the view that any tampering with existing African boundaries, however arbitrary some might seem, threatens to open a Pandora’s box of tribal, ethnic and linguistic tensions. The rest of the world has followed the Union’s lead and has so far refused to recognise Somaliland’s independence. The irony is striking. While the international community recognises the failed state of Somalia, with dozens of al-Shabaab bases and a government that barely functions, free, democratic and peaceful Somaliland remains a country that does not exist.

Which may go some way to accounting for the slight air of unreality. Somaliland is the size of Greece with the population of Berlin. People are fond of saying that Hargeisa, the capital city, is a village but the truth is that the whole country has the kind of intimacy that comes from so many people being linked by bonds of blood or friendship. Government ministries are full of cousins and schoolmates. When I dropped in on the head of the Supreme Court — in chambers as cosy as those of an English country solicitor — he turned out to be a former student of my guide.

As for tourists, you won’t run into many. If you have reached the point where the packaged nature of modern tourism has begun to pale, Somaliland may be the antidote. In one of the region’s most fascinating countries, peak season sees 50 tourists a month. This is barely tourism at all but more the kind of quirky, heartwarming travel that would have delighted Evelyn Waugh. Facilities are modest but everywhere I stayed was comfortable and clean and, if you have a taste for goat, Somaliland is culinary heaven.

. . .

A goat herd in the Golis mountains, near Sheikh

I spent almost a week in the country, travelling from Borama in the northwest to the delightful town of Sheikh, high on an escarpment in the Golis mountains. I trawled over obscure tombs in desert landscapes, I was received at a university like a visiting royal and I had tea with elderly gentlemen in roadside cafés who reminisced shamelessly about British rule. I picked my way through the ruins of a colonial villa that could have been as ancient as Nineveh, I chatted to shepherds in biblical cloaks and I learnt a few of the 40 or so Somali words for camel, each defining a different age, use, gender or condition. Everywhere I went, I was welcomed with genuine warmth.

In Hargeisa market I went in search of the money-changers in preparation for a tour upcountry. Between the outdoor tailors and a roadside blacksmith with goatskin bellows, I found Madam Sada, enthroned on a white garden chair behind several mountain ranges of Somaliland shillings. Impressive in a scarlet direh, the all-enveloping outer garment worn by most Somali women, Madam Sada had an air of authority the governor of the Bank of England would envy. I asked if she had ever been robbed.

“Who would be a thief?” she declared, gesturing to the other money-changers, and the passing crowds. “We all know one another.”

©Panos

A bread-seller in Hargeisa

While I was sorting out the cash flow, Mahmud was round the corner scoring the drugs. On the road out of town towards the Gulf of Aden — one of only two asphalt roads in the country — he initiated me into the brethren of qat chewers. Pronounced “chat”, it is the tipple of choice in these regions, a leaf chewed by everyone from tea ladies to government ministers. It is legal and hardly more intoxicating than a couple of glasses of wine but for the initiate it can be hard work. With a lapful of twigs and a cheekful of bitter green leaves, I felt I was trying to eat a privet hedge.

Mahmud was my bodyguard, part of a security scheme instigated by the government, desperate to distance itself from the reputation of the other Somalia. There is little evidence that such precautions are necessary here, and many people suspect it is just a bit of a money-spinner. But for Mahmud, it was the dream assignment — an air-conditioned Toyota, an undemanding foreigner, a small wedge of expenses money and limitless opportunities for qat chewing.

. . .

As the last outposts of Hargeisa fell away, the sky opened and the landscape unwound towards distant horizons. Children waved from the thorny corrals of nomad tents. Here and there goats browsed, standing on their hind legs to reach the tender leaves of the acacia. Two women strode across an empty plain, their direhflapping like bright banners in the dun-coloured expanses.

In a desert so vast and so apparently simple, the eye is drawn to details — streaks of mineral colour in the rocks shifting from crimson to yellow, a scarf of cloud uncurling from a distant escarpment, the brittle acacia trees soaking their feet in tiny pools of shade. Gerald Hanley, a British colonial official in this forgotten corner of empire, found these landscapes thrilling and humbling. “To wake up at first light, a flea on a prairie of rock and sand, each morning,” he wrote in Warriors and Strangers (1971), “is to realise that one’s own importance is something one highly overrates.”

©Panos

A market in Hargeisa

We left the main road and followed tracks north through rough hilly country. A monitor lizard scuttled into the cover of thorn bushes. Termite mounds, taller than a man and as convoluted as a Gaudi spire, stood sentinel along the tracks. After a time we came to a desert wadi, where pools of seasonal water lingered in the river bed.

Thousands of years before Mohammed, before Christ, even before Moses, a settled and prosperous community lived in this valley. In the rock overhangs that once served as shelters, we can still admire their home decorations. Swarming across the ceilings and walls of their open-sided caves are complex paintings, polychromatic figures of people and animals, among which are antelope and giraffe, hinting at different savannah landscapes. Central to the paintings are decorated cattle with prominent udders and lyre-like horns. Their glorification on these ancient walls is reminiscent of the cattle herders of east Africa, the Maasai and the Samburu, who still sing to their cows.

It is an indication of Somaliland’s isolation that this spectacular site was not discovered until 2002. Experts reckon the paintings are anywhere between 5,000 and 10,000 years old. Interest in prehistoric rock art is often limited to its antiquity. But Laas Geel is different; everyone rates it as among the most beautiful rock art in Africa. And it is art, not mere representation. The pictures have a visual language. They are trying to say something, to transmit meaning. They are stylised, fluid, celebratory.

Some day at Laas Geel there may be a coach park and a visitor centre. There may be ropes and guides and closing times. But for now Mahmud and I sat in the open-sided caves, overlooking the valley, alone with the prehistoric world. Surrounded by the beautiful paintings of their beloved cattle, it was easy to sense the ghosts of the distant people who had lived here, chatting, laughing, complaining around their cooking fires, enjoying the same view — the weaver birds fluttering between the bushes, the camels coming to drink at the pools in the riverbed, the low sun raking across the valley.

. . .

Berbera

Laas Geel signalled some subtle change in the landscape. On the road to the port of Berbera the desert softened. The acacia scrub grew thicker and greener until the road was positively tree-lined. Night fell with equatorial suddenness. When the lights of Berbera appeared, they floated in the distance like an old liner making slow passage up the Gulf of Aden.

I stayed in a hotel a mile or so from town, inhabited chiefly by UN staff and development workers. It stood on Berbera’s spectacular beach, which, anywhere else in the world, would be lined with sunloungers, noisy cafés and resort hotels. The following morning, walking alone along the ocean’s edge, I encountered a train of spectral camels emerging from the white glare of early sun and surf.

The camels were on their way to market. Berbera’s livestock market — the fattened animals are shipped across the Gulf of Aden to the Arabian peninsula — is the last echo of its role as one of the great trading ports of the Arabian Sea. In the 19th century, merchants from across the Indian Ocean travelled here for coffee, gum, myrrh, ostrich feathers, livestock and slaves.

A chap from the ministry of tourism arrived to show me round the old merchant’s quarter. Abdi was a Berbera native, and we were unable to go a hundred metres without greeting a cousin, a neighbour, a friend, a love interest.

Built a century ago by Arab and Indian traders, the merchants’ houses had aspirations to elegance, with shuttered windows and first-floor galleries. Most were now abandoned. Tea houses had moved into the ground floors while squatters had taken up residence in the high-ceilinged rooms upstairs.

In one of the tea houses, a radio was playing. “Listen,” Abdi said. “Do you hear that song? It is a famous Somali story, known by everyone. And it took place here, in this street.”

With a lapful of twigs and a cheekful of bitter green leaves, I felt I was trying to eat a privet hedge

A boy brought us glasses of sweet tea as Abdi, Mahmud and I sat in rickety chairs in the middle of the sand street. On the corner children played with a deflated football while a goat nosed beneath a tree.

In the early years of the last century, the building opposite us was a bakery, Abdi explained. It was run by the Boodhari family. Every day a beautiful young woman came to buy the family bread. Her name was Hodan Cabdulle, and the baker’s son, Elmi, fell hopelessly in love with her. But it was a love of which he could never speak. In those days marriages were arranged. She came from an important family; he was a humble baker.

“But Elmi was a poet as well as a baker,” Abdi said, “and he wrote about his love. His poems made the story famous. All Somalis know this Romeo and Juliet story. That song, just now on the radio, that was one of his poems.”

What happened to Elmi? I asked.

“To make him forget Hodan, his family brought a dozen beautiful and eligible young women in the hope he would choose one as a wife. He refused them all. The experience was the inspiration for perhaps his most beautiful poem — ‘If beauty could act, or calm a heart . . .’ Elmi eventually died of a broken heart.”

“And what happened to Hodan?”

“She married — someone more appropriate to her background, someone her family approved of,” Abdi said. “She had nine children. I am one of them. Hodan is my mother.” It was typical of the intimacy of Somaliland that the man telling me this famous story should turn out to be Hodan’s son.

The story of Elmi Boodhari resonates beyond this street, and this shuttered bakery. Elmi is credited with changing the course of Somali literature. He allowed it to grow beyond a heroic warrior tradition to something more personal, more introspective. His poetry has become emblematic of Somaliland, a country that has turned away from the warrior tradition of its troublesome brother to forge a new and more peaceful identity.

SOURCES: Financial Times