The young priest Robert Bolenge* could not have imagined the poverty he would find when he arrived at his new post in Yaligimba in 2002. The district lies at the heart of vast oil palm plantations belonging to Feronia Inc., in the northeast of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

“I had never witnessed such suffering before,” says Bolenge. “I couldn’t have imagined that someone could work so hard with a basket tied to his back, cutting down palm bunches all day, and only take home about $20 a month.”

(*Not his real name. Click here to listen to an interview with the pastor in French.

You can also read a transcript in English.)

Under Belgian colonial occupation (1908-1960), land was stolen from communities all along the length of the Congo River to establish oil palm plantations. Now, the communities have launched a determined effort to get their land back. But the company occupying their lands today is expanding its activities with funding from the world’s biggest development finance institutions and multilateral banks – despite these agencies’ stated commitments to support the rights of local people.

A simmering, 100-year old land conflict in the war-torn Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is about to boil over.

In the name of “development”

Development finance institutions (DFIs) were created by northern governments to provide financing for high risk projects in so-called developing countries. Their role is to provide public money for private ventures that would otherwise struggle to raise capital for projects where the anticipated returns in terms of poverty alleviation are high.

Today these government-controlled institutions provide upwards of $100 billion to private companies operating in developing countries, which is equivalent to almost two thirds of official development assistance.1 A growing share of these funds are targeted at companies operating in the food and agriculture sector.2

Northern governments equipped their DFIs with codes and standards to guard against corruption and human rights violations in countries where they operate. These policies are meant to prevent DFIs from investing in companies that grab land, violate labour rights or engage in corrupt practices.

So how did several of the world’s most prominent DFIs come to own Feronia Inc., a Canadian agribusiness company that people in the DRC say is illegally occupying their land, subjecting them to horrific work in plantations and leaving their communities destitute? There is also evidence that Feronia has engaged in financial practices that violate the anti-corruption policies of its DFI owners.

If the DFIs have a blacklist, Feronia should be on it. Instead, multilateral banks and the development finance arms of the United States, UK, France and Spain have poured millions of dollars into Feronia since 2012. DFIs now own over 70 percent of the company.

Colonial roots

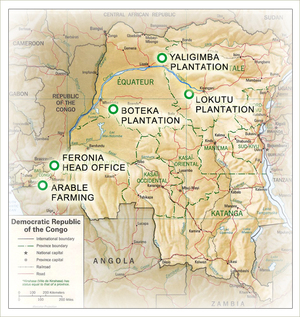

In the early 20th century, Belgian colonial officials started to explore the possibilities of establishing oil palm plantations along the Congo River, in what are now the Equateur and Oriental Provinces of the DRC.

“The Belgians took all these lands without a single legal document.” – Gaspard Bosenge-Akoko, member of the Orientale Provincial Parliament. (Photo: GRAIN)

“When the Belgians first came, they saw that the forests were full of high-yielding wild oil palms and they began asking local chiefs for one or two hectares in exchange for some bags of salt,” says Gaspard Bosenge-Akoko, an elected member of the Oriental Province parliament.

“They found the lands to be very fertile, and so they started grabbing more and more land and they cleared them of all but the oil palms so that they could establish plantations. The indigenous people were forced onto smaller areas, called reserves, where they were told that they could continue with their traditional practices. But today, even these reserve lands have been taken over. They took all these lands without a single legal document.”

Belgian oil palm plantation development was backed by King Leopold’s brutal colonial forces and financed by the Lever brothers. The brothers built up oil palm plantations near the villages of Lokutu and Yaligimba in Oriental Province and Boteka in Equateur Province. The plantations would eventually fuel a food processing empire and lay the foundations for the development of one of the world’s largest food corporations – Unilever.

Unilever held onto its oil palm plantation business throughout the 20th century until 2002, when, with war raging in eastern Congo, it decided to pull out of the country. That year, it sold its consumer products subsidiary, Marsavco, to a Pakistani business family with deep roots in the DRC. Then, in 2009, after several years of neglect, it sold its oil palm plantations in Boteka, Lokutu and Yaligimba to Feronia Inc., a little known company registered in the Cayman Islands with no previous experience in the palm oil sector.3

Map showing location of Feronia plantations in DRC. (Feronia)

Unilever’s plantations were held through a Congolese company called Plantations et Huileries du Congo SARL (PHC) that was 24 percent owned by the DRC government. In 2009, Feronia Inc acquired Unilever’s 76 percent share in PHC by paying $3,854,551 to a Unilever holding company in the Netherlands. The company’s directors then took Feronia Inc public on the Toronto Stock Exchange in 2010 in order to finance its continued operations.

Over the next few years, Feronia racked up tens of millions of dollars in losses and its stock price tanked, from around $4 when it opened in September 2010 to less than a dollar by November 2013. The company would likely have collapsed completely had it not been for a startling rescue by several major multilateral banks and development finance institutes.

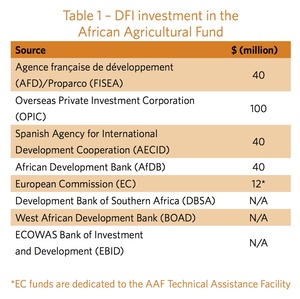

In December 2012, Feronia announced that the African Agricultural Fund (AAF) had agreed to purchase 20 percent of the company’s shares for $5 million through its subsidiary, African Agriculture Fund LLC. The AAF is a Mauritius based fund managed by the Mauritian private equity firm Phatisa. It was established in 2009 to channel money from multilateral banks and development finance institutes into agribusiness companies in Africa in order to “combat the chronic undercapitalisation in the African agribusiness and food sectors.”

The AAF has DFI investment from France, US, and Spain as well as the African Development Bank and several other African multilateral banks. The Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA) is listed as a “promoter” of the fund, while the European Commission and the Italian Cooperation Agency finance the AAF’s Technical Assistance Facility.4

The other major DFI investor in Feronia is the UK government’s CDC Group plc, formerly the Commonwealth Development Corporation. The CDC made its first investment in Feronia in November 2013, spending $14.5 million to take 27.5 percent of Feronia’s shares and providing the company with an additional $3.6m convertible loan facility to support the implementation of an Environmental and Social Action Plan. Then, in January 2015, it invested $7 million to take its ownership of Feronia up to 48 percent.

Today, the AAF and the CDC control over 70 percent of Feronia’s shares, while the DRC government retains its 24% stake in PHC, Feronia’s DRC oil palm plantations subsidiary.

Unilever’s role

Unilever advertises itself as a champion of socially responsible business. But its “sustainable living plan” clashes badly with its behaviour in the Congo.20

(Photo: Belgeo Revue)

In 1911, the Belgian state granted Unilever (then Lever Brothers) control over 67,800 square kilometres of land in the Congo to establish plantations to feed its rapidly expanding multinational food processing business. Unilever went on to occupy and exploit communities in the DRC for 100 years.21 Then, in 2002, it suddenly cashed out and sold its consumer goods company Marsavco to the Rawji Family and later its plantations to Feronia in 2009.

Unilever made $3.8 million from the sale to Feronia. This money was channelled into its offshore Dutch subsidiary. It also collected millions more in proceeds from the sale of some of its villas and other properties. These flowed into Unilever’s Dutch accounts tax free after Feronia pressured the DRC government into waiving $3 million in taxes under tax holiday provisions meant for actual foreign investment.

Around 800 administrative staff lost their jobs when Unilever sold Marsavco and left the DRC. It also left owing these workers at least $24 million in unpaid wages. For the last 13 years they’ve been struggling to get that money from Unilever. The Supreme Court of the DRC ruled in their favour in 2007, but the money has yet to reach them.22 Earlier this year, some of the former workers went on a hunger strike in desperation.

Almost all of the palm oil produced by Feronia is still sold to Marsavco, and the former Marsavco workers insist that Unilever is still very much involved, behind the scenes. One piece of evidence of this involvement is the label on Marsavco’s Blue Band margarine containers, which reads: “Produced on behalf of Unilever” (“Produit pour le compte de Unilever”)

An illegal occupation

When Feronia acquired PHC from Unilever in 2009, it claimed to have inherited lease agreements from PHC for all of the lands where the company has plantations. Feronia said it had “revolving 25-year leases” covering 101,455 ha at Lokutu, Boteka and Yaligimba, which expire at different times between 2017 and 2030 and which have a renewal cost of $1,000 per lot, with lots varying from a few hectares to 2,000 ha.

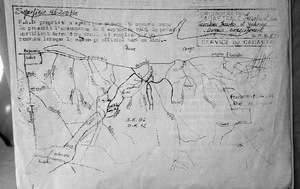

Yet community leaders at the company’s Lokutu plantations say that the only document that Feronia or Unilever have ever shown them as evidence of the company’s rights to the 63,000 ha concession it claims is an old registration certificate that is riddled with errors and that does not confer any legal title.

Registration certificate for the Lokutu concession.

“All they have is a falsified certificate of registration, signed by an incompetent surveyor,” says the provincial deputy, Gaspard Bosenge-Akoko. “Can you imagine a company grabbing over 40,000 ha of land from these communities, depriving them of their agricultural activities, on the basis of this kind of flimsy document?”

On March 8, 2015, over 60 customary chiefs and other community leaders from across the district of Yahuma, where 90 percent of Feronia’s Lokutu plantations are located, gathered in the town of Mozité to call for the resolution of their longstanding grievances against Feronia. They say the company has never consulted them about the use of their lands and has no right to be there.

“We demand, first and foremost, the start of negotiations to reclaim our rights over the lands that have been illegally taken from us over the past 104 years,” they stated in a declaration signed during the meeting.

“We want to be compensated, and only afterwards can we proceed to discussions over a memorandum of understanding for a new contract.”

March 2015: participants at the meeting in Mozité, Yahuma District.

At its Boteka plantations, local leaders explained to RIAO that Feronia signed a concessionary agreement with the government of the DRC in 2012 establishing the company’s rights to use the 15,000 ha former Unilever concession for agricultural purposes. However, the local communities say they were never consulted about the agreement, as is their legal right, and that they have never negotiated terms to the contract, as is also their right. They say that only a few local authorities (chefs de secteur) gave their authorisation, without the participation and consent of the customary chiefs or the local communities.6

In a letter sent to the president of the DRC in August 2013, the customary chiefs of the Territory of Ingende, where the Boteka plantations are located, wrote:

This company arrived in our Territory in 1912 during the colonial occupation. In 1947 it received a 25 year renewable lease, and not a perpetual contract as is insinuated in the behaviour of the managers of the company. A collective contract was signed, in one way or another, with our elders around a year ago and ever since, our community has been excluded from any decisions regarding the expansion of the concession and other activities and has only suffered from the negative impacts of the plantations, such as the disappearance of caterpillars, mushrooms, wild animals, freshwater fish, and, overall, the near complete loss of the flora and fauna. This has resulted in severe malnutrition amongst our children and even our elders; the mortality rate for infants and mothers during childbirth is amongst the highest in the province.

There’s also the important question of whether it is legal for Feronia to control any land in the DRC at all. As Feronia’s DFI backers know very well, the DRC passed a new Law on the Funadmaental Principles of Agriculture (loi portant principes fondamentaux relatifs à l’agriculture) on June 24, 2012 that states, under Article 16, that land can only be attributed to companies that are majority owned by national investors. Feronia has so far chosen to ignore this law, telling its investors that it “has been and continues to be involved in discussions with various levels of government in the DRC regarding the interpretation of the law.”7

A brutal “system”

During the ten years that Pastor Bolenge has been in Yaligimba, he has been a witness to the harsh regime laid down by Feronia.

“All the lands the communities had were taken by the company, so they have nowhere to grow their own food,” he says. “At one point, I started encouraging them to plant crops and raise livestock in the abandoned areas of the plantation. But when it was time to harvest, the company destroyed all the crops and ordered the people out by force. It’s as if the company wants to ensure that the people stay dependent on it for their survival. It’s like a system of slavery.”

The villagers say that even the most minor transgressions are brutally punished by the company’s guards. Anyone caught carrying just a few nuts fallen from the oil palms is fined or, in many cases, whipped, hand cuffed and taken to the nearest prison.

People from the village of Yalifombo, inside Feronia’s Lokutu plantations, say that about a year ago the company’s guards caught a local boy named Papy Yve carrying a small amount of palm nuts. He was detained, whipped and then taken to prison in the city of Kisangani. At some point, however, he disappeared and has not been seen since. The villagers say his family fled the village to hide on one of the Congo River islands, fearing that the company would target them.

Having lost their traditional forests and farmlands,, the communities within the areas of Feronia’s plantations have little choice but to work for the company, and few get access to anything but the lowest paying jobs. The people of Bayolo, in the District of Yahuma, say that 90 percent of the people working for the company from their village are poorly paid labourers, who receive no benefits: no housing, no medical services, no education, no potable water. Indeed, the Yahuma leaders says that the last time someone from their district worked for the company as a manager was in 1964.

Community members and other local sources that GRAIN and RIAO spoke with at the Boteka and Lokutu plantations maintain that the daily wage for a typical labourer in Feronia’s Lokutu plantations and nurseries is about 1,400 francs congolais (US$1.50), which is below the country’s minimum daily wage of 1,680 FC.8

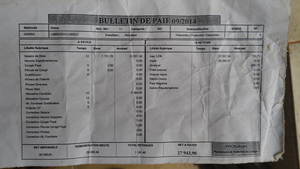

Although payslips of some workers at the Lokutu plantations indicated amounts paid of 1,750 FC, these were per unit of work, not per day. As explained by the villagers that GRAIN and RIAO spoke with, a “unit” of work is something few, if any, workers can complete in a day.

The Yalifombo villagers working in Feronia’s Lokutu plantations say the company expects them to harvest about 80 large bunches of palm nuts per day to be considered to have completed a unit’s work, while workers in the nursery have to fill and transport around 600 seedling sacs to complete what the company considers to be a day’s work. A day’s task, they say, is too much for most workers to complete in a single day.

A payslip for a worker at the Lokutu plantation showing just 12 units were completed in the month of September, 2014. (Photo: GRAIN)

Some at the Lokutu plantation even hire others as “porters” or get their children and other family members to help them complete their daily tasks.

To make matters worse, the company often pays its workers late. Representatives of local civil society organisations that support communities in Feronia’s Lokutu plantations say that wages can go unpaid for 3-4 months. This makes it extremely difficult for workers to make ends meet and leaves them vulnerable to loan sharks. They say that managers of the company use an illegal system of debt bondage, known as “ikotama”, to force workers to work on weekends and holidays in order to pay off high interest debts.

Civil society organisations from the Lokutu area have documented numerous other labour abuses, such as the lack of contracts between the company and most workers, safety issues with pesticides and the violation of mandatory work hours.

Shady dealings

“The Corporation applies a ‘zero tolerance’ approach to acts of bribery and corruption.” – Ravi Sood, Chairman of Feronia Inc.

One of the key people that has been involved in Feronia from the beginning is Barnabe Kikaya bin Karubi, the DRC’s Ambassador to the UK since August 2008 and, prior to that, President Joseph Kabila’s Private Secretary and Minister of Information

Kikaya served on the Board of Directors of Feronia from its inception until some point in 2014 when he was quietly dropped from the Board.

For his services as director, Kikaya was paid the company’s standard annual fee of $10,000-20,000 per year.

But these were not the only payments made to Kikaya. Buried within the company records that Feronia is obliged to disclose as a Toronto Stock Exchange listed company is evidence that, Feronia paid Kikaya a total of nearly $3 million in cash and shares during his time as director with the company.9

Some of these payments were made to Kikaya as annual rental fees of between $120,000-150,000 for the lease of a “house and apartment in Kinshasa” located at Kikaya’s family residence.10 The biggest payout was orchestrated through Feronia’s Cayman Islands subsidiary as part of the initial purchase of PHC.

When Feronia purchased PHC from Unilever, the deal was structured through Feronia JCA Ltd of the Cayman Islands. This Feronia subsidiary was, for unspecified reasons, 20 percent owned by a DRC-based company called Jean Colette Afrique Sprl, which is wholly owned by Kikaya.

As soon as the deal with Unilever went through, Feronia Inc acquired Kikaya’s share of Feronia JCA in exchange for the issuing of 8,894,344 shares in Feronia Inc, valued by the company at over $2.2 million. The deal included the acquisition of a farm from Kikaya, which Feronia says is worth over US$600,000.11 This farm asset, however, does not appear on Feronia’s books after its mention in its September 2010 financial statements.

Big payouts are not unique to Kikaya. Even though the company has lost millions of dollars in every year of its existence and has failed to provide its workers and their families with a minimal level of compensation, the managers and directors of Feronia have lined their pockets. In 2011, for example, the Chairman of Feronia, Ravi Sood, received $150,000 in cash and $101,000 in share-based awards, and a company owned by his wife received $131,000 for “corporate development services”. In 2010, her company was paid $256,754 for the supply of services and expenses.12

In 2010, James Siggs, then Feronia’s CEO, was paid $616,000 in fees and share options. When he was replaced as CEO the following year, he received a compensation package of $317,379. Even Feronia’s accountant, Georgina Cotton of the UK, got a hefty $306,000 in total compensation in 2010.13 That year the top four managers raked in around $1.5 million in fees, about 1,000 times the average annual pay for 4 of their plantation workers.

Responsible investment on paper, land grabbing in practice

Feronia and its DFI shareholders all have policies and standards addressing environmental and social issues, working conditions and financial integrity.

Feronia has a “zero-tolerance” policy on corruption. The African Development Bank’s operational safeguard on involuntary resettlement requires its clients to show that they have broad community support for activities that displace or alienate them from their lands. The CDC, for its part, has a detailed Code of Responsible Investing that requires it to “promote appropriate corrective actions” when its portfolio companies are involved in any serious incidents resulting in “a material adverse environmental or social impact, or material breach of law relating to environmental, social or business integrity matters.”

Workers at the oil palm plantation at Lokutu (Photo: Feronia)

Beyond their own policies and standards, Feronia and its DFI owners are also collectively committed to adhere to the World Bank Group Environmental, Health and Safety Guidelines; the Round Table for Sustainable Palm Oil Principals and Criteria for the Production of Sustainable Palm Oil; the World Bank’s IFC Performance Standards on Environmental and Social Sustainability; the Uniform Framework for Preventing and Combating Fraud and Corruption; the IFC Corporate Governance Development Framework; the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises; and the ILO Forced Labour Convention.14

All of these policies and safeguards are supposed to be strictly adhered to and enforced by the DFIs. Spain’s AECID, for instance, adopted a Code of Conduct for Responsible Investment (Código de Financiación Responsable) in 2013 that prohibits the AECID from “investing in any activity that involves an unacceptable risk to contribute to or be complicit in activities or omissions that violate its principles, such as human rights violations, corruption or negative social or environmental impacts.”15

The CDC’s January 2015 subscription agreement with Feronia requires, in detail, that Feronia’s operations not be the subject of any environmental, social or land claims. One of the conditions of the agreement is that “there are no disputes regarding boundaries, rights, covenants or other matters relating to any Property or its use.”16

Where client companies violate these principles and policies, most of the DFIs involved in financing Feronia have mechanisms through which affected communities can submit their grievances. It is yet to be seen, however, whether these grievance mechanisms will actually hold the DFIs to account for their investments in Feronia, if and when communities come forward with petitions.

One of the difficulties in the case of Feronia is that a third of its shares are held by funds of the private equity firm Phatisa, which manages DFI investment money through its African Agricultural Fund (AAF). Multilateral banks and DFIs have yet to clarify the extent to which their policies and safeguard mechanisms apply to such third party transactions, despite the increasing use of third party fund managers by DFIs and the increasing calls for accountability on these transactions.

The AAF does have a Code of Conduct for Land Acquisition and Land Use, an Anti Bribery and Corruption Policy and a Tax and Transparency Policy that should have been applied in its decision to invest in Feronia. Phatisa has, however, refused to make these policies public, saying that it is “bound by confidentiality undertakings”.17

Ironically, AAF’s main backer, the French government, through its Agence Française de Développement (AFD) and AFD’s private sector finance arm Proparco, has been leading an international effort to develop standards and transparency for large-scale agricultural projects.

In October 2014, the AFD released an “Ex-ante analysis of agricultural and land investment projects: Operational guide” (Guide d’analyse ex-ante de projets d’investissements agricoles à emprise foncière: Guide opérationnel). Jean-Marc Gravellini, AFD’s Director of Operations, says the AFD has already started to use this guide and is encouraging other financial institutions to follow suit.18

The AFD guide calls on investors to assess the “nature” of a company before investing in it.

“Does it have previous experience in the agribusiness sector? If so, how did it acquire the lands on which it operates? Has the use of these lands been subject to conflicts or opposition by local communities leading to violence? Does the structure of the company risk facilitating tax evasion, risk reducing legal responsibility and risk undermining legal restrictions on the transfer of rights to the land?”

It appears that none of these questions were adequately considered in the AAF investment in Feronia.

Moreover, AFD and Proparco had previously published an “Analysis of agricultural and land investment projects” (Grille d’analyse de projets d’investissements agricoles à emprise foncière) in 2010 to orient their participation in agribusiness projects. The investment in Feronia violates the number one principle laid out in this document, which requires all AFD and Proparco investments to “respect the rights of the users of the land, whether their rights to the land are formal or informal (customary/traditional), individual or collective.”19

Taking back what’s theirs

The local people living within the Feronia plantations have the neighbouring communities as visible evidence of how the company’s plantations have impoverished their lives. Their neighbours have forests and farmlands that provide them with food, medicines and livelihoods. These forests are rich with wild oil palms, and all along the Congo River communities can be seen processing oil from these palms, and transporting it by small boat (pirogue) to nearby markets where it is always in high demand.

The villagers say that Feronia and Unilever promised them time and again that the plantations would improve their lives, that they would get good jobs, schools, modern homes, health clinics, and decent roads. But the communities have seen few if any of these benefits in the hundred years that their lands have been occupied by plantations. They are fed up with the company’s promises. They are tired of slaving away on the plantations and watching the palm oil harvested from their lands flow out of their communities to enrich a handful of company bosses.

Villagers say Feronia and Unilever promised the plantations would improve their lives, but they have seen few benefits from a century of occupation.

“Enough suffering!” says the Grand Chief of Yahuma. “We no longer want tears; we want this company to disappear, and we will do what’s necessary to resolve our own problems”

At the behest of its DFI investors, Feronia has now hired consultants to carry out an Environmental and Social Assessment of its palm oil operations. The assessment will undoubtedly result in a new round of promised improvements, some of which may in fact be implemented. But the assessment will not result in what the communities want and what they have full rights to demand: the return of their lands.

“When we make demands for our rights to be respected, the company sends us delegations, but nothing ever changes,” said a local prefect at a meeting of community leaders in the village of Mozité, Yahuma District in March 2015. “We don’t want anymore distractions. If the company can’t meet our demands, then they must leave and give us back our lands and forests, the lands of our ancestors. We are forest people and we can live fine without them. Everyone here needs to take back their share.”

Feronia is now owned by DFIs that have a public mandate to support “development” and policies that oblige them to respect the rights of local communities to their lands (see Box 2). The DFIs that own Feronia need to do the right thing: give the people of the DRC back their lands and compensate them for the years of suffering they have endured and the wrongs this 100-year old colonial enterprise has committed.

Produced in collaboration with Fundación Mundubat, War on Want, Association Française d’Amitié et de Solidarité avec les Peuples d’Afrique, World Rainforest Movement, Food First, SOS Faim and CIDSE

Notes

1 María José Romero, “A private affair: shining a light on the shadowy institutions giving public support to private companies and taking over the development agenda,” Eurodad, 2014.

2 APRODEV, “Policy Brief: The Role of European development finance institutions in land grabs,” mai 2013 (en anglais)

3 For a more detailed account of Feronia’s early history, see GRAIN, Feeding the 1%, October 2014.

4 “The purpose of this facility is to provide technical assistance to agri and food related businesses that receive investment through the AAF, allowing them to create new opportunities for smallholder farmers, farmer business groups and rural communities”. The US$13.3 million TAF is financed primarily by the EC. See the AAF TAF website:http://tinyurl.com/ozy9krb

5 Feronia press release, 8 November 2013.

6 This information was gathered by RIAO through conversations with local community leaders.

7 “Feronia provides update on DRC Agricultural Law“, 3 July 2013. The text of the law is available here: tinyurl.com/m95zvst.

8 The minimum wage established in 2008 is 1,680 FC. See Journal Officiel de la Republique Democratique du Congo.

9 Information on payments made to Kikaya and the proceeding details of Feronia Inc’s activities are available through official company documents provided by SEDAR under the listings Feronia Inc, G.T.M Capital Corporation, and Difference Capital Inc.

10 Only in the Feronia Management Discussion and Analysis of May 2, 2011, is it specified that this payment is for a property in Kinshasa. The address is 32 Allée Verte, Mbinza Ma Campagne, C/Ngaliema, Kinshasa, DRC. This is also the address listed for Kikaya with another Canadian company he is involved with: Ressources Shamika Inc.

11 Feronia Inc., Interim Consolidated Financial Statements, September 30, 2010.

12 It’s important to note that Sood also collected management fees for the funds he managed that provided much of Feronia’s initial investment capital. For the nine month period ended September 30, 2009, TriNorth Capital paid LAM management fees of $168,597 and for the same period in 2008 it paid $400,772: See tinyurl.com/pqqh3zr

13 The above financial information is detailed in GRAIN, Feeding the 1%, October 2014.

14 Feronia says it “is working towards certification by the Roundtable for Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO) and is implementing IFC/World Bank standards for environmental and social sustainability.” See “”Feronia Inc. Reports 2014 Results,”, Market Wire, 27 April 2015,

15 The original Spanish: “no financiará ninguna actuación que comporte un riesgo inaceptable de contribuir o ser cómplice de actuaciones u omisiones que vulneren estos principios, tales como violaciones de derechos humanos, corrupción, o daños medioambientales y sociales.”

16 Another condition relates to corruption: “Neither the Corporation nor any of its Subsidiaries nor, to the knowledge of the Corporation, any of their directors, employees or agents has, in connection with the business, committed any Corrupt Acts.” The Purchase of Convertible Debentures Subscription Agreement between the CDC Group PLC and Feronia Inc of January 22, 2015 is available on SEDAR.

17 Personal communication from Stuart Bradley, Senior Partner, Phatisa, 17 April 2015.

18 “D’ores et déjà, le groupe AFD a commencé à utiliser ce guide. Il faut souhaiter que les autres institutions financières aillent dans le même sens.” – Jean-Marc Gravellini, directeur des Opérations du groupe AFD.

19 Le respect des droits des usagers du foncier, qu’ils soient formels ou informels (coutumiers/ traditionnels), individuels ou collectifs, doit être un préalable aux investissements

20 See Unilever’s website, “Our strategy for sustainable business“

21 For an account of the history of Unilever’s plantations in the Congo, see: Dr Fadjay Kindela, “Recycling the past: rehabilitating Congo’s colonial palm and rubber plantations,” Mongabay, 11 September 2006.

22 “RDC: le combat de treize ans de salariés d’Unilever,” RFI, 2 May 2014.